Case scenario

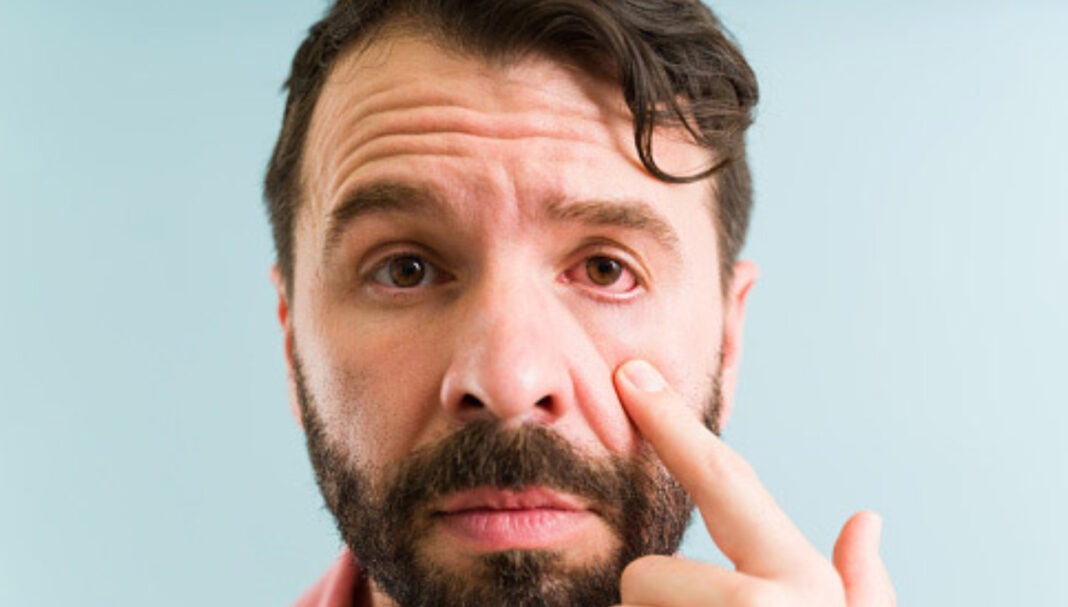

Kon is a student and resident of a shared university dormitory who has come into your pharmacy complaining of red and ‘icky’ eyes. He mentions it started yesterday and that it was a little difficult to open his eyes this morning. He describes some discomfort but not pain. You rule out any red flag symptoms such as photophobia or vision changes and ensure he does not have symptoms suggestive of more sinister bacterial infection. Kon is otherwise well and does not use corrective eyewear. He tells you that one of his friends had red eyes last week.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

Competency (2016) Standards addressed: 1.1, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 3.1, 3.2, 3.5. Accreditation expiry: 31/01/2027 Accreditation number: CAP2402OTCLB |

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Introduction

Conjunctivitis is a common ophthalmic condition characterised by inflammation of the conjunctiva.1,2 Cause

THIS IS A CPD ARTICLE. YOU NEED TO BE A PSA MEMBER AND LOGGED IN TO READ MORE.