Case scenario

This educational activity was managed by PSA at the request of and with funding from GSK, Sanofi and CSL Seqirus.

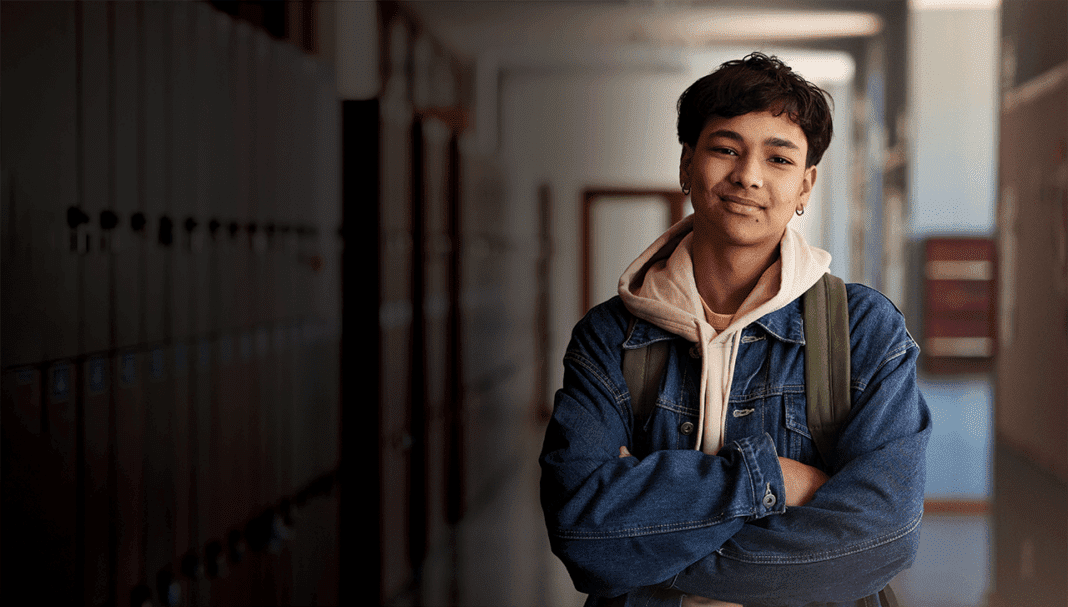

Kushal is a 16-year-old male who missed his dTpa vaccination in 2021 due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neither Kushal nor his mother fully understand the importance of vaccination or the diseases that this vaccine protects against.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

Competency standards (2016) addressed: 1.1, 1.4, 1.5, 3.1, 3.5 Accreditation number: CAP2503SYPNB Accreditation expiry: 29/02/2028 |

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Introduction

Immunisation has reduced disease, disability and death from 26 infectious diseases. While Australia has a relatively high imm

THIS IS A CPD ARTICLE. YOU NEED TO BE A PSA MEMBER AND LOGGED IN TO READ MORE.