Case scenario

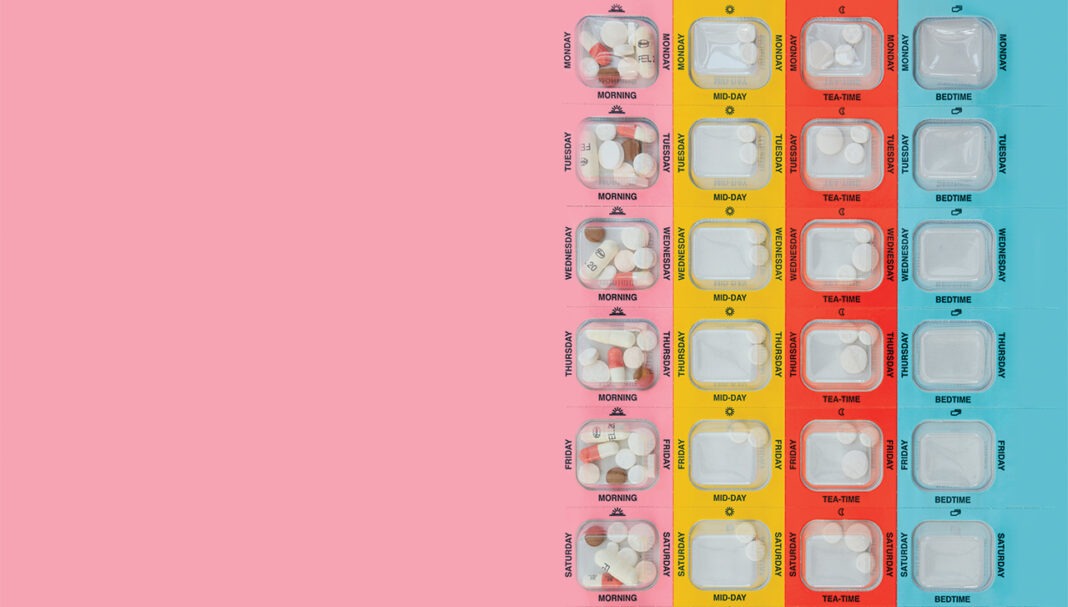

Mrs Johnson, a 65-year-old patient with hypertension, comes to the pharmacy to fill her repeat prescriptions for perindopril 4 mg and amlodipine 5 mg. You notice that Mrs Johnson is getting her repeats dispensed irregularly and offer her a blood pressure (BP) check. Mrs Johnson mentions that her BP has been poorly controlled, and she often forgets to take her medicines.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

Competency (2016) standards addressed: 1.1, 1.4, 1.5, 3.1, 3.5 Accreditation code: CAP2412SYPAQ Accreditation expiry: 30/11/2027 |

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Introduction

Missed or delayed administration of prescribed doses is a common concern in clinical practice and can be viewed under the framework of non-adherence, either intentional or unintentional. Medication adherence refers to the extent to which a person’s behaviour matches with the agreed recommendations from a health care provider.1 Adherence to prescribed dosing regimens is crucial for achieving the best therapeutic outcome.

Understanding the implications of missed doses and how

THIS IS A CPD ARTICLE. YOU NEED TO BE A PSA MEMBER AND LOGGED IN TO READ MORE.